Galesburg, Illinois

Galesburg, Illinois | |

|---|---|

Main Street (US Hwy 150) in downtown Galesburg | |

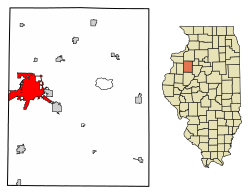

Location of Galesburg in Knox County, Illinois | |

| Coordinates: 40°57′08″N 90°21′10″W / 40.95222°N 90.35278°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Knox |

| Township | Galesburg City |

| Founded | 1837 |

| Founded by | George Washington Gale |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Peter Schwartzman (G)[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 17.94 sq mi (46.45 km2) |

| • Land | 17.76 sq mi (45.99 km2) |

| • Water | 0.18 sq mi (0.46 km2) |

| Elevation | 771 ft (235 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 30,052 |

| • Density | 1,692.21/sq mi (653.38/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 61401 |

| Area code | 309 |

| FIPS code | 17-28326 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2394842[1] |

| Wikimedia Commons | Galesburg, Illinois |

| Website | www |

Galesburg is a city in Knox County, Illinois, United States. The city is 45 miles (72 km) northwest of Peoria. At the 2010 census, its population was 32,195.[4] It is the county seat of Knox County[5] and the principal city of the Galesburg Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Knox and Warren counties.

Galesburg is home to Knox College, a private four-year liberal arts college, and Carl Sandburg College, a two-year community college.

A 496-acre (201 ha) section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Galesburg Historic District.

History

[edit]Galesburg was founded by George Washington Gale, a Presbyterian minister from New York state who had formulated the concept of the manual labor college and first implemented it at the Oneida Institute near Utica, New York. In 1836 Gale publicized a subscription- and land purchase-based plan to found manual labor colleges in the Mississippi River valley.[6] Land was purchased for this purpose in Knox County and in 1837 the first subscribers to the college-founding plan arrived and began to settle what would become Galesburg.[7]

Galesburg, populated from the first by abolitionists, was home to one of the first anti-slavery societies in Illinois and was a stop on the Underground Railroad.[8] The city was the site of the fifth Lincoln–Douglas debate. held on October 7, 1858. Galesburg also was the home of Mary Ann "Mother" Bickerdyke, who provided hospital care for Union soldiers during the Civil War.

In later years, Galesburg became the birthplace of poet Carl Sandburg, artist Dorothea Tanning, and former Major League Baseball star Jim Sundberg. Sandburg's boyhood home is maintained by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency as the Carl Sandburg State Historic Site. It includes the cottage he was born in, a modern museum, the rock under which he and his wife Lilian are buried, and a performance venue.

Throughout much of its history, Galesburg has been inextricably tied to the railroad industry. Local businessmen were major backers of the first railroad to connect Illinois's then two biggest cities—Chicago and Quincy—as well as a third leg initially terminating across the Mississippi River from Burlington, Iowa, eventually connecting to it via bridge and thence onward to the Western frontier. The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) sited major rail sorting yards here, including the first to use hump sorting. The CB&Q also built a major depot on South Seminary Street that was controversially torn down and replaced by a much smaller station in 1983. The yard is still used by the BNSF Railway.

In the late 19th century, when the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway connected its service through to Chicago, it also laid track through Galesburg and built its own railroad depot. The depot remained in operation until the construction of the Cameron Connector southwest of town[9] enabled Amtrak to reroute the Southwest Chief via the Mendota Subdivision and join the California Zephyr and Illinois Zephyr at the Burlington Northern depot. A series of mergers eventually united both lines under the ownership of BNSF Railway, carrying an average of seven freight trains per hour between them. With the closure of the Maytag plant in 2004, BNSF is once again the largest private employer in Galesburg.

Galesburg was home to the pioneering brass era automobile company Western, which produced the Gale, named for the town.[10]

Galesburg was home to minor league baseball from 1890 to 1914. The Galesburg Pavers was the last name of the minor league teams based in Galesburg. Galesburg teams played as members of the Eastern Iowa League (1895), Central Interstate League (1890), Illinois-Iowa League (1890), Illinois-Missouri League (1908–1909) and Central Association (1910–1912, 1914).[citation needed]

Baseball Hall of Fame members Grover Cleveland Alexander (1909) and Sam Rice (1912) played for Galesburg. Rice had to leave the Galesburg team in 1912, when his wife, two children, his parents and two sisters were killed in a tornado. Galesburg teams played at Illinois Field (1908–1912, 1914), Lombard College Field (1908–1912, 1914) and Willard Field at Knox College (1890, 1895).[11][12][13][14]

Lombard College was in Galesburg until 1930, and is now the site of Lombard Middle School.

The Carr Mansion at 560 North Prairie Street was the site of a presidential cabinet meeting held in 1899 by U.S. President William McKinley and U.S. Secretary of State John Hay.

Geography

[edit]Galesburg is in western Knox County. Interstate 74 runs through the east side of the city, leading southeast 47 miles (76 km) to Peoria and north 36 miles (58 km) to Interstate 80 near the Quad Cities area.

According to the 2010 census, Galesburg has a total area of 17.928 square miles (46.43 km2), of which 17.75 square miles (45.97 km2) (or 99.01%) are land and 0.178 square miles (0.46 km2) (or 0.99%) are water.[15]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Galesburg, Illinois (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1896–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

71 (22) |

86 (30) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

112 (44) |

102 (39) |

100 (38) |

94 (34) |

79 (26) |

70 (21) |

112 (44) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 30.0 (−1.1) |

34.7 (1.5) |

48.0 (8.9) |

61.3 (16.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

81.2 (27.3) |

84.0 (28.9) |

82.3 (27.9) |

76.2 (24.6) |

63.0 (17.2) |

48.0 (8.9) |

35.4 (1.9) |

59.7 (15.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 21.9 (−5.6) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

38.0 (3.3) |

50.6 (10.3) |

61.8 (16.6) |

71.6 (22.0) |

74.7 (23.7) |

72.8 (22.7) |

65.5 (18.6) |

52.8 (11.6) |

39.0 (3.9) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

50.2 (10.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 13.8 (−10.1) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

39.9 (4.4) |

51.7 (10.9) |

62.0 (16.7) |

65.4 (18.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

54.7 (12.6) |

42.5 (5.8) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

40.7 (4.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−28 (−33) |

−14 (−26) |

9 (−13) |

24 (−4) |

36 (2) |

42 (6) |

41 (5) |

19 (−7) |

17 (−8) |

−6 (−21) |

−22 (−30) |

−28 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.69 (43) |

1.87 (47) |

2.39 (61) |

3.83 (97) |

5.27 (134) |

4.58 (116) |

4.04 (103) |

3.89 (99) |

3.85 (98) |

2.82 (72) |

2.60 (66) |

2.14 (54) |

38.97 (990) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.0 (23) |

6.6 (17) |

2.3 (5.8) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.7 (4.3) |

5.9 (15) |

25.9 (66) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.9 | 6.9 | 8.7 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 7.0 | 8.8 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 104.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.0 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 3.3 | 14.3 |

| Source: NOAA[16][17] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 323 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,953 | 1,433.4% | |

| 1870 | 10,158 | 105.1% | |

| 1880 | 11,437 | 12.6% | |

| 1890 | 15,264 | 33.5% | |

| 1900 | 18,607 | 21.9% | |

| 1910 | 22,089 | 18.7% | |

| 1920 | 23,834 | 7.9% | |

| 1930 | 28,830 | 21.0% | |

| 1940 | 28,876 | 0.2% | |

| 1950 | 31,425 | 8.8% | |

| 1960 | 37,243 | 18.5% | |

| 1970 | 36,290 | −2.6% | |

| 1980 | 35,305 | −2.7% | |

| 1990 | 33,530 | −5.0% | |

| 2000 | 33,706 | 0.5% | |

| 2010 | 32,195 | −4.5% | |

| 2020 | 30,052 | −6.7% | |

| Decennial US Census | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[18] | Pop 2010[19] | Pop 2020[20] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 27,688 | 25,114 | 21,088 | 82.15% | 78.01% | 70.17% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 3,402 | 3,630 | 4,215 | 10.09% | 11.28% | 14.03% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 64 | 56 | 47 | 0.19% | 0.17% | 0.16% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 345 | 284 | 301 | 1.02% | 0.88% | 1.00% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 8 | 7 | 7 | 0.02% | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 25 | 39 | 172 | 0.07% | 0.12% | 0.57% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 486 | 828 | 1,670 | 1.44% | 2.57% | 5.56% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,688 | 2,327 | 2,552 | 5.01% | 6.95% | 8.49% |

| Total | 33,706 | 32,195 | 30,052 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2000 Census

[edit]As of the census[21] of 2000, there were 33,706 people, 13,237 households, and 7,902 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,994.9 inhabitants per square mile (770.2/km2). There were 14,133 housing units at an average density of 836.5 per square mile (323.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 84.23% White, 10.20% African American, 0.22% Native American, 1.03% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 2.46% from other races, and 1.84% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.01% of the population. 17.4% were of German, 12.6% American, 11.5% Irish, 11.3% Swedish and 9.1% English ancestry according to Census 2000.

There were 13,237 households, of which 26.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.6% were married couples living together, 12.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.3% were non-families. 34.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.87.

The population was spread out, with 21.1% under the age of 18, 11.8% from 18 to 24, 27.0% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 18.1% 65 or older. The median age was 38. For every 100 females, there were 100.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,987, and the median income for a family was $41,796. Males had a median income of $31,698 versus $21,388 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,214. About 10.7% of families and 14.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.4% of those under age 18 and 6.3% of those age 65 or over.

Festivals

[edit]Galesburg is the home of the Railroad Days festival, held on the fourth weekend of June.[22] The festival began in 1977 as an open house to the public from the then Burlington Northern. Burlington Northern gave train car tours of their yards. The city started having street fairs to draw more people to town. In 1981, the Galesburg Railroad Museum was founded and opened during Railroad Days. For a while, the city and the railroad worked together on the celebrations. In 2002, the railroad backed out of the festival and there were no yard tours. In 2003 the city worked with local groups to revamp the festival and the Galesburg Railroad Museum resumed bus tours of the yards. The Galesburg Railroad Museum has continued to provide tours of the yards since then. In 2010, the Galesburg Railroad Museum started offering a VIP tour of the yards, in which a select group of riders are allowed in the Hump Towers and Diesel Shop and see the BNSF at work. During the festival, one of the largest model railroad train shows and layouts in the U.S. Midwest happens during Railroad Days at the new Galesburg High School Fieldhouse.[22]

During Labor Day weekend in September, Galesburg hosts the Stearman Fly in.[23] Also in September are the Great Cardboard Boat Regatta and the Annual Rubber Duck Race, at Lake Storey.[24][25] On the third weekend of every August, a Civil War and pre-1840s rendezvous is held at Lake Storey Park.

Transportation

[edit]Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service from Chicago on four trains daily. It operates the California Zephyr, Carl Sandburg, Illinois Zephyr, and Southwest Chief daily from Chicago Union Station to Galesburg station and points west. The Southwest Chief and the state-supported Carl Sandburg and Illinois Zephyr take passengers to Chicago or points west, while the California Zephyr discharges passengers only on its eastbound run since the other trains provide ample service.

Galesburg Transit provides bus service in the city. There are four routes: Gold Express Loop, Green Central Loop, Red West Loop, and Blue East Loop.[26] BNSF provides rail freight to Galesburg and operates a large hump yard 1.9 miles (3.1 km)[27] south of town.[28]

Galesburg is served by Interstate 74, which runs north to Moline in the Quad Cities region, and southeast to Peoria and beyond. The Chicago–Kansas City Expressway, also known as Illinois Route 110, runs through Galesburg. To the southwest it passes through Macomb, the home of Western Illinois University, and toward Quincy, before crossing into Missouri. Galesburg served is served by U.S. Routes 34 and 150. US 34 connects Galesburg to Burlington, Iowa, and Chicago. It is a freeway through its entire run in Galesburg and west to Monmouth. It connects to Galesburg through three interchanges at West Main Street, North Henderson Street, and North Seminary Street, along with an additional interchange at Interstate 74. US 150 runs through the heart of Galesburg. It enters the city as Grand Avenue from the southeast, runs through downtown as Main Street, and exits the city as North Henderson Street. Galesburg is additionally served by Illinois State Route 97, Route 41, Route 164, and Knox County highways 1, 7, 9, 10, 25, 30, 31, and 40.

Galesburg Municipal Airport provides general aviation access, while Quad City International Airport and General Wayne A. Downing Peoria International Airport provide commercial flights.

Galesburg will be home to the National Railroad Hall of Fame. Efforts are underway to raise funds for the $30 million (~$43.6 million in 2023) project, which got a major boost in 2006, when Congress passed a bill to charter the establishment. It is hoped that the museum will bring tourism and a financial boost to the community. Construction of the museum began in 2019.[29]

Media

[edit]Galesburg has several radio stations and newspapers delivering a mix of local, regional and national news. WGIL-AM, WAAG, WLSR-FM and WKAY-FM are all owned by Galesburg Broadcasting while Prairie Radio Communications owns WAIK-AM. KZZ66 provides Weather Information for NOAA Weather Radio in the Galesburg area.

The Galesburg Register-Mail is the result of the merger of the Galesburg Republican-Register and the Galesburg Daily Mail in 1927. The two papers trace their roots back to the mid-19th century. A daily, it is the main newspaper of the city, and was owned by Copley Press until it was sold to Gate House Media in April 2007. The Zephyr was started in 1989, was published on Thursdays and was the only locally owned newspaper until its final edition December 9, 2010. The New Zephyr began publication in early 2013. It is published every Friday. The Knoxville Bulletin is a weekly newspaper established in May 2016. It is owned by Limestone Publishing.

Galesburg is part of the Quad Cities television market.

FM radio

[edit]- 90.7 WVKC "Tri States Public Radio", supported by Western Illinois University and Knox College Tri States Public Radio[30] (NPR Affiliate with HD Radio subchannels)

- 92.7 WLSR "92.7 FM The Laser", Active Rock (RDS – Artist/Title)

- 94.9 WAAG "FM 95", Country (RDS – Artist/Title)

- 95.7 WVCL, Religious, an affiliate of Three Angels Broadcasting Network

- 100.5 W263AO (Translates 91.5 WCIC), Christian AC (RDS)

- 105.3 WKAY "105.3 KFM", Adult Contemporary (RDS – Artist/Title)

AM radio

[edit]Web radio

[edit]- KGB-Radio "Knox Galesburg Radio", Galesburg Area News Weather and Maps

- The Paper, local weekly (free) newspaper (in the Register-Mail every Wednesday)

- Register-Mail, local daily newspaper

- The Zephyr, local weekly newspaper (discontinued in 2010)

- The New Zephyr, local weekly newspaper (on hiatus as of December 2013)

- Knoxville Bulletin, local weekly newspaper (started in May 2016)

- The Burg, local weekly newspaper (started in summer of 2019)

Popular culture

[edit]

- Galesburg is the birthplace of George Washington Gale Ferris Jr., inventor of the Ferris wheel.[31]

- According to legend, the four Marx Brothers (Groucho, Chico, Harpo, and Gummo) first received their nicknames at Galesburg's Gaity Theatre in 1914. Nicknames ending in -o were popular in the early 20th century, and a fellow vaudevillian, Art Fisher, supposedly bestowed them upon the brothers during a poker game there. Zeppo Marx received his nickname later.[32]

- Barack Obama mentioned Galesburg during his keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention and near the beginning of his 2010 State of the Union Address.[33] Obama also visited Galesburg High School in 2011 to speak to students while in the area for a Midwestern bus tour.[34]

- Baseball legend Jimmie Foxx lived out some of his last years as a greeter at a steakhouse in Galesburg. Foxx left just before his death in 1967.[35]

- Ronald Reagan attended second grade at Silas Willard Elementary School between 1917 and 1918.[36] He portrayed pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander in the movie The Winning Team in 1952, starting with Alexander's stint with the minor-league Galesburg Boosters.[37]

- Galesburg is the birthplace of artist Stephen Prina, whose recent publication Galesburg, Illinois+ documents an exhibition that portrays the town indirectly through various media.[38]

- The first stage of the NES game Ninja Gaiden is in Galesburg, depicted as more like New York City.[39]

Notable people

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Galesburg, Illinois

- ^ "Mayor - Mayor - Peter Schwartzman - City of Galesburg, IL". www.galesburg.com/. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Galesburg city, Illinois". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 25, 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Gale, George Washington (1836). "Circular and Plan". Knox College. Archived from the original on December 15, 2014.

- ^ Forssberg, Grant. "The Origins of Knox College". Knox College. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ "Underground Railroad Freedom Station – Galesburg Colony at Knox College". Knox College. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Cherrington, Rex (June 20, 1996). "Did Galesburg businessmen really need to pay to bring the Santa Fe Railway to Town?". The Zephyr. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877-1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.51.

- ^ "Register Team Encyclopedia". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Sam Rice | Society for American Baseball Research". sabr.org.

- ^ "Tom Wilson: Fond memories of Galesburg baseball emporiums". The Register-Mail.

- ^ Wilson, Tom. "WILSON: Life in Galesburg's minor league baseball". The Register-Mail.

- ^ "G001 – Geographic Identifiers – 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Galesburg, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Galesburg city, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Galesburg city, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Galesburg city, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "Schedule for 2010". galesburgrailroaddays.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "National Stearman Fly-In – Official Website". www.stearmanflyin.com. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "Great Cardboard Boat Regatta-Canceled – Galesburg, IL – Sep 10, 2016". www.eventcrazy.com. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "Galesburg Public Schools Foundation – Annual_Rubber_Duck". Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Galesburg Transit City Bus". Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Map". Google Maps. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ Trains Magazine (July 8, 2006). "North America's Hump Yards". Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Construction on Galesburg National Railroad Hall of Fame to Begin in 2019". Associated Press. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ http://tspr.org/ Tri States Public Radio: NPR news and diverse music serving west central Illinois, southeast Iowa, and northeast Missouri

- ^ "George Ferris biography, birth date, birth place and pictures". Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ "Knox Baseball Trounces Actors". Archived from the original on December 4, 2008.

- ^ Wikisource

- ^ "Obama Bus Tour Stop #12: Galesburg, IL". cnn.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Daniel, W. Harrison (January 2004). Jimmie Foxx. McFarland. p. 206. ISBN 9780786418671.

- ^ Silas Willard main page Archived 2011-08-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hoots, Joshua. "The Winning Team". Motion Picture. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ Stephen Prina: Galesburg, Illinois+. Schriften des Museums Kurhaus Kleve. Vol. 70. Köln: Walther König. 2016. ISBN 9783863359287.

- ^ NINJA GAIDEN INSTRUCTIONS (PDF). Tecmo. March 1999. p. 11.

Further reading

[edit]- Broughton, Chad (2015). Boom, Bust, Exodus: The Rust Belt, the Maquilas, and a Tale of Two Cities. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199765614.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Community Development Department

- CarlSandburg.net: A Research Website for Sandburg Studies

- Carl Sandburg Historic Site Association

- The Galesburg Project lists famous Galesburgers and visitors. Links to Galesburg history articles

- Galesburg Railroad Days

- Railroads in the Midwest: Early Documents and Images

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Lincoln-Douglas Debate in Galesburg Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- 1994 reenactment of Lincoln-Douglas Debate in Galesburg televised by C-SPAN (Debate preview and Debate review)

- Local papers:

- The Register-Mail (daily)

- The Zephyr (weekly, discontinued 2010)

- The Paper (weekly, free)

- The Burg (weekly)